| c | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|

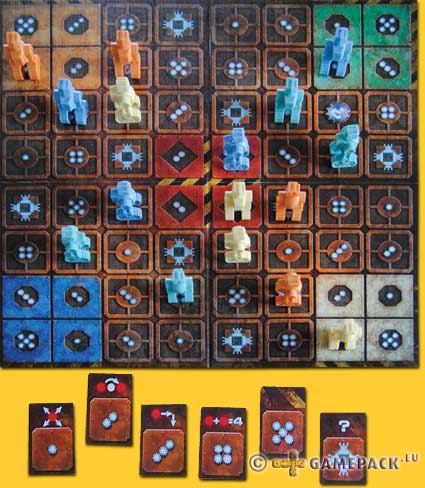

RoboRama |  |

|||||||||||||||||||||

| 11.09.15 In RoboRama the players have to guide their robots to the opposite site of the board; not unlike the principle of Halma. Instead of standard pawns the pieces are rather impressive robots, and they are moved by playing numbered cards. The cards indicate the number of steps the robot may be moved. Robots move in a straight line only, and they are allowed to jump over other robots of the same colour. Once played, the card becomes temporarily inactive. But, if a robot ends its movement on a square with a number depicted that corresponds to the number on one of the already played cards, this card is re-activated and ready for use on a future turn. There is also a chip-card that allows re-activation of a card of your choice. The first player to bring all his four robots to the other side of the board wins the game. There are two variants: in the first one, each numbered card has an additional feature, for example to divide the movement points over multiple robots, or to move diagonally. This variant makes the game more strategic and is advisable if you are looking for a bigger challenge. The second variant introduces the so-called ChaosBot, a neutral robot that can be moved by any of the players using a separate set of cards to cause mayhem. Unfortunately this makes the game a lot tougher and lengthier. RoboRama may be fun for younger players, but the aficionado will probably look elsewhere. RoboRama, Dennis Kirps & Gérard Pierson, PlayThisOne, 2014 - 2 to 4 players, 8 years and up, 45 minutesxxtop |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

| c | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Patchwork | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| 31.08.15 It’s possibly not your most favourite pastime in real life: sewing together pieces of leftover cloth into a quilt. But like it or not, this is what the two players are going to do with 33 patches in all shapes and sizes. Needle and thread are not required, but a selection of buttons and some time do come in handy. The players each have an empty quilt board of 9x9 squares. The so-called patches that have to be assembled on this board consist of two or more of these squares. The aim of the game is to fill up the quilt board to the maximum, since penalty points will be awarded at the end of the game for each empty square. The patches are placed randomly on the table in a large, stretched oval shape; the neutral playing figure is placed next to the smallest shape. In the centre of the oval, the time board is placed. Both players place their marker on the starting space of the time track. The starting player may choose to buy any of the three patches in front of the neutral playing figure (in clock-wise direction), but he has to be able to pay for it! Each patch depicts is costs in buttons – players start with five buttons each- but also in time, representing the amount of labour needed to add the patch to your quilt. That can be a difficult decision: one shape fits very well on the quilt board, but is very expensive, and the other patch costs a lot of time. There’s no connection between the costs/time and the size or shape of the patch. One six-square-sized patch costs two buttons and one time, while another six-square-sized patch in a slightly different shape costs 10 buttons and five time! Once the decision has been made, the neutral figure moves to the now vacant position in the oval, and as a consequence, other patches become available for purchase. The player also advances on the time board; if he is still lagging behind his competitor, he takes another turn. That’s all very nice, but at a certain moment he’s only allowed to choose form patches he can’t afford. Now what? Instead of purchasing a patch, he may advance his time marker until he’s on the position just in front of the other player; he then takes buttons from the supply according to the number of spaces he just moved. Another way to receive income is to pass the positions on the time board that depict a button symbol. Many of the patches already have buttons sewn on; when a player passes a button-symbol on the time board, he takes buttons according to the number of buttons depicted on the patches on his quilt board. At a certain moment both players reach the end of the time track. When that moment arrives, they both count their buttons and subtract two buttons ‘penalty’ for each empty square on their quilt board. The player with the most buttons wins the game! Patchwork is the odd man out in Uwe Rosenberg’s oeuvre, who made one nice card game ‘Bohnanza’ before he went berserk on the heavy development games: Agricola, Le Havre, Arler Erde and so on. All games with a plethora of rules, and material. Patchwork proves that a good game can also be simple! Patchwork, Uwe Rosenberg, Lookout Games, 2014 - 2 players, 8 years and up, 30 minutes |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

| c | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Royals | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| 12.05.15 Are you familiar with the expression ‘to curry favour with a person’? Well, that is exactly what the players are trying to do in this quick and simple game. The board depicts a part of Europe, where Britain, France, Spain and the German States are the key players. In the role of 17th century noble houses, the players aim to occupy influential positions in several cities of the aforementioned countries. The requirements for occupying a position are depicted on the board, and it’s very simple: just play a number of cards of the corresponding country. Every position has its own status within the country, so it is quite obvious that a lower position (marshal, baron) requires very few cards, while the higher positions (princess, king) are more demanding. But in return, the higher positions also give you more influence. On his turn, a player always draws up to three cards, and additionally he may choose to play cards to claim a position, or just save his cards for later. For the king’s position, as many as eight country cards are required, so it may take some turns to acquire them! (But all hamsters out there, beware: there is a card limit!) The claimed position is demonstrated by placing a cube in the player’s colour. Additionally, he places a cube on the portrait of the corresponding person next to the board. When the drawing pile is exhausted, a scoring phase takes place: in each country, the influence points of the players are added up. The player with the most influence and the runner-up receive victory points, all other players remain empty-handed. A new round begins, and the players continue their flattery and other subtle attempts to gain influence. They can even throw their opponents into disrepute by playing an intrigue-card, which effectively means that they have to vacate their position. Of course the accusing player can claim the vacant position for himself, if he plays the corresponding country cards. The intrigue cards form a separate deck; if a player decides to draw one, he is allowed to draw only one additional country card (instead of the usual three cards per turn). As soon as a player occupies at least one position in every city of a country, he may take the Country bonus. And if a player occupies all seven different titles (marshal, baron, countess, duke, cardinal, princess, king) he receives the Nobel House bonus. After three scoring phases, the game is over, but not before points have been awarded for majorities on the seven title scoring markers. The player with the majority of cubes on each title gets the full points; in case of a tie, the points are divided. This can be taken literally, since the title scoring markers consist of two jigsaw-parts. All the points collected during the game are added up, and the winner can be announced. Royals is a quick and simple game: draw cards, play cards, next player! Everything is transparent, the atmosphere is pleasant; what else could we wish for? Care for another game? Royals, Peter Hawes, Abacusspiele, 2014 – 2 to 5 players, 10 years and up, 60 minutesxxtop |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

| c | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Pagoda | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| 12.05.14 In turn, two players jointly build on pagodas with which they earn points: from 1 point for ground level pillars to 4 points per pillar on the fourth floor and 6 points when a pagode is completed with a roof. To be able to do this, colour cards are played of which five are on display at each of the players. The players have two further cards in their hands. Each turn up to three pillars and an unlimited amount of floors may be build; in this respect counts a roof as a pillar. To be allowed to place a pillar, a matching colour card must be placed. When starting a pagoda, any colour pillar may be placed; after this the next three pillars must match that colour. When the four pillars of a floor have been placed, the next floor may be placed. This floor must have the same colour as the colours of the pillars supporting it but may otherwise be freely chosen. This new floor holds the outlines and colour of four new pillars; when building any further on this pagoda these pillars must follow the colour of the newly laid floor. The players also have a player board with special actions that become active when a player has placed a floor in a specific colour. These actions then become available and can be done twice until a new floor of that colour is placed. The actions vary from being allowed to play two colour cards for any other colour, to building four pillars in a turn instead of three. The game ends when three pagodas have been build. Players almost always will go for scoring the most points in a turn; it will therefore not happen very often that a player will start a new pagoda instead of continue to build on an existing one. Usually a game has four pagodas that are built, of which three are completed. The game meanders peacefully forth: a player plays cards and scores, and then the other player does likewise. The cards of a player on display are hardly an obstacle or consideration for the other player whether or not to build. The game lacks the viciousness of Babel or Kahuna, for example, two excellent two player games in which players can thwart each other on several occasions. Because of its flatness and meaninglessness Pagoda certainly will not be placed on the list of outstanding monuments, and therefore will quickly be overgrown with moss. Not all what the Hippodice Spieleclub awards is distinctive... Pagoda, Arve D. Fühler, Pegasus Spiele, 2014 - 2 players, 8 years and up, 30-45 minutesxxtop |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

| c | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Packet Row | ||||||||||||||||||||||

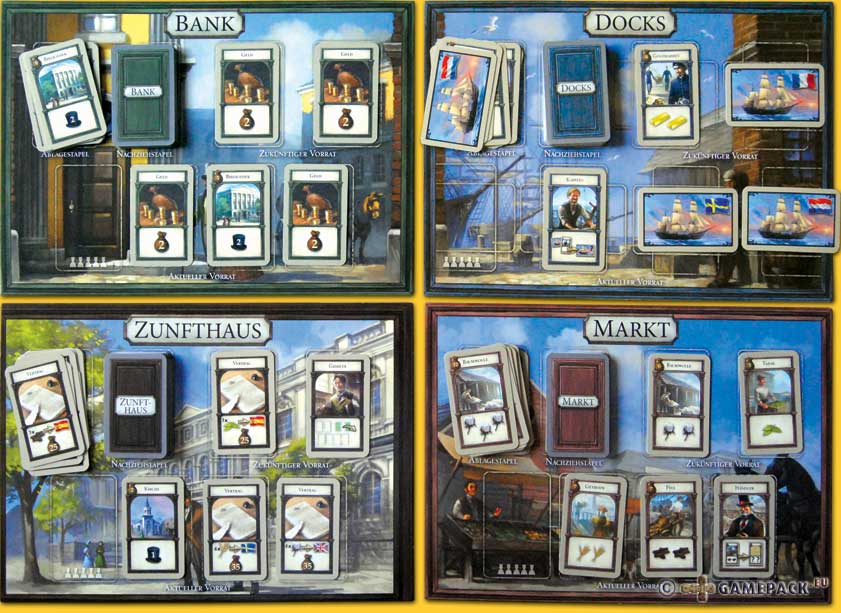

| 27.11.13 With Packet Row we are ready for the second episode of the series 'excuse parts': the large location boards could just as well have been left out, or be part of the deck of cards to indicate the four locations; each of the four deck of cards has its location on its back anyway, so it's instantly clear that it is about the docks, or the guild house, the market or the bank. With this game box, we're dealing again with a lot of excessive air! Grab a smaller game box and try if it fits the cards and coins; it already works with the box of Jaipur. Dear publishers, we understand that you'd like to use a large box for sales purposes, to distinguish yourself on the shelf in the stores, but our shelf space is quite limited and besides: shouldn't there be a moral limit on how much air a box may contain that furthermore -as the costs of the cards are in no proportion to the sales price- acts as an excuse to justify the price? Shouldn't that be part of fair trade too, after all? Shipping goods is what is to be done in the game, and orders filled. Filling an order earns money, and with this real estate can be bought; these buildings have various point values that added up determine the winner at the end of the game. Each player starts with an order and 25 money. At each of the four locations depending on the amount of players a couple of cards are in display. Depending on the location this mainly are order, ship, resource or money cards. Each location also has five different character cards in the stack with which a special action can be conducted. Furthermore, at each location are two cards in the display that give insight at what cards will be on display in the following round. For example, an order card requires the shipping of three pieces of cotton with a Spanish ship. So, a player will have to get to the market for cotton -if this card is in the display- and go to the harbour to hire a Spanish ship -again: if the card is in the display. And acquiring a card is not that easy: altough the starting player acting as harbor master chooses the location, all other players may perform an action there first: buy a card or take one, before the harbor master himself takes his turn and take the cotton or Spanish ship. When the targeted card already has been taken, the harbor master may decide to pass at this location and choose another location. Players who already have taken an action must pass; in a round only one card can be acquired. When all players except the harbor master have taken a card, the harbor master may choose another location -if it was not already the fourth- and buy or, if no costs are involved, take a card there. Built in nasty little thing number two: when all players except the harbor master have passed at the current location and hope for an other and maybe better location, the harbor master in his turn could take or buy a card, ending the round immediately. So it is important for the harbor master to assess the needs of the other players as well as possible, but all other players must carefully consider what to do too. This mechanism in fact is the heart of the game as without it there would be nothing new under the sun. When one or more -depending on the amount of players- stack of cards are depleted, the game ends and the points for the acquired buildings are counted. When a player has to switch his focus from filling orders to buying buildings is a matter of anticipation; in any case, once a building has been bought the money no longer can be used to buy goods at the market. The beautiful illustrations by Michael Menzel support the warm atmosphere of the game. It is a pleasure to look at all small details on the cards; even the cardboard coins have that rich feeling. The assistant in the guild house even has a lighting à la Vermeer; very nice! The constant bidding at locations where a player has little or no interest, or where he can whistle for it because an other player has taken the card right before his nose, make the game a rather dull and casual affair that also takes too long. There are no highlights, there is no tension; everyone gathers what he should and could, and then the points are counted. Packet Row, it's a heavy title for an average ligthweight game with a low entry level that however only manages to captivate shortly, of which on top of it its sales price is ten euros too high. Packet Row, Åse & Hendrik Berg, Pegasus Spiele, 2013 - 2 to 5 players, 10 years and up, 45-75 minutesxxtop |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

| c | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Pyramidion | ||||||||||||||||||||||

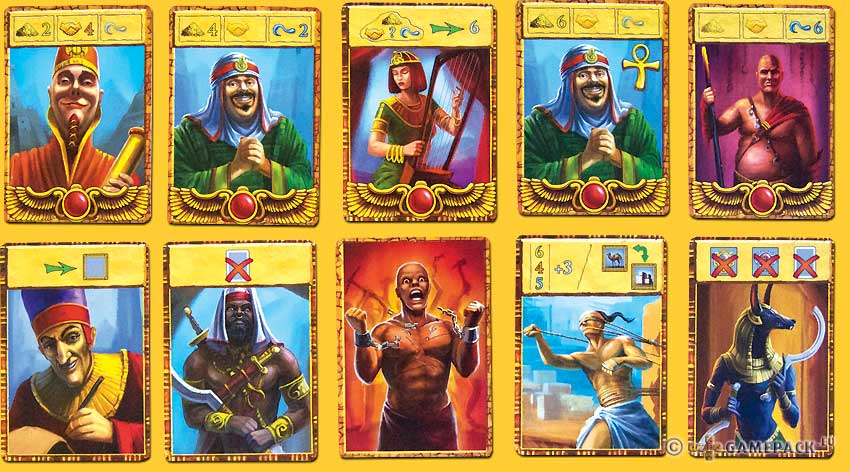

| 03.02.13 We are fictionally transported to ancient Egypt, an experience not wholly unfamiliar to anyone who regularly plays board games. Our goal is to make the greatest contribution to the construction of the pyramid of Gizeh, with the reward being the honor of placing the last block of stone (Pyramidion) atop the pyramid! We start each round with a handful of character cards. These either give us a number of points in one or more of the three categories (influence, negotiation or trade) or have some sort of special ability. There are eight sites to be fought over. The distribution card drawn determines which of these locations get goods placed on them. Also 5 boat cards are drawn, ready to be loaded with goods. They require 2 to 6 specific goods and bring 1 to 5 victory points. The starting player picks the first site to activate. Then all players, starting with the player who has activated the site, have the choice of either playing a card from their hand or passing. A player who has passed can’t play any more cards at this site. This goes on until everyone has passed. Then for each player the number points they have played in the categories influence, negotiation and trade is counted. If a player has the highest amount of points in a category (joint highest does not count) and at least the minimum amount required for that site he gets a reward: the player with the highest trade can take all the goods currently on the site, the player with the highest influence can place a torturer token on the site, and the player with the highest negotiation can place a negotiator token. As each site can only contain one torturer and one negotiator, previously placed tokens of the same kind are discarded. A torturer token allows the use of one good type produced at that site when loading the ships, while the owner of a negotiator token can take a good from that site at the start of the next round. Then the next player chooses a site, and so on until each player has activated two sites. The sites also have special powers: the player activating Karnak receives a ‘personal’ boat that he can attempt to load this round, in Alexandria anyone who plays a card with an Ankh symbol can take one good of their choice from the supply. Finally the players get the opportunity, in player order, to load one of the available boats with the goods required. You can then place the boat card face-down in front of you, those points are secured! If you have the right goods and there are boats left over when the turn comes back to you, you could even load another boat. At this point, if one or more players have at least 10 victory points, the player with the most points is declared the winner. Otherwise new boats, goods and character cards are made available and a new round begins. The bidding mechanism in Pyramidion vaguely brings to mind that of Tadsch Mahal. Both can have one thinking at times: “I have already invested so many cards in this site; I should have something to show for it! Then I’ll throw in a couple more!” But this has none of the elegance or subtlety of the Knizia classic. “Bam! I remove the card that gives you 8 trade!” “Oh yeah? Then I’m playing a revolt card, so practically no one will get anything here!” And after you have finally been able to place a token somewhere through painstaking effort and at a cost of two thirds of your cards, the first player playing an Ankh symbol in Cairo can immediately remove it again. So we keep bidding on the sites, endlessly and pointlessly, until someone has loaded enough boats to end the game. Pyramidion is one of those games that make you wonder what exactly it adds to the considerable amount of games already out there. Is there anyone breathlessly waiting for yet another unremarkable game with an Egyptian theme? In any case, it will take a slave driver with a big whip to convince us to consider playing it again! Ugur Donmez Pyramidion, Yannick Gervais, White Goblin Games, 2012 - 2 to 54 players, 10 years and up, 60 minutesxxtop |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

| c | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Rattus Cartus | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|

15.12.12 An influence track for six disciplines and some stack of cards. Oh, and rats, although we don’t really want them. We are noblemen scrolling through the country looking for followers. We do this by placing a disc on a building card, in player order playing from zero to any amount of population and special cards. In general: the player who played the most population cards may perform the comprehensive action; all other players in that building play the restricted action; all proceed on the influence track for the corresponding category as they played population cards, but for each card that does not match the category for this building, a player has to take one rat token. At the end of the game points are scored for each of the six categories, accumulated gold and some small stuff such as having the most population cards in a player’s hand. After this the accumulated rat tokens are compared with a row of five blind cards that was formed at the start of the game; the pink tokens on these cards at least have to equal each player’s rat collection, otherwise that player cannot qualify for an eventual victory. |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

| c | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Qubix | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| 04.11.12 The English subtitle qualifies Qubix as 'an abstract game'. So, we are not builders, garden architects or mosaic artists in the early-Victorian era, where we have to stretch our imagination to the very limit to be able to discover the promised theme in the game. It is just an abstract game. A large cube is constructed from blocks in three different sizes and five different colours. You can do this according to the scheme in the rulebook, or you can construct it yourself. This cube represents the main warehouse. In his turn, a player may take one block from the cube and place it on a three-by-three construction area on one of the player boards, or store it temporarily in his personal three-by-one warehouse. Only blocks that are accessible from above and from at least one side may be removed from the main warehouse. The colour of the block is of no importance at this point, and is also not related to a player's colour. The aim is to create certain patterns of one colour on the construction areas. If a player creates a pattern on his own construction area he scores the indicated number of points, but if the pattern was created on another player's construction area, the owner of the construction area also receives some points. So, players are allowed to build on each other's construction areas. As a consequence, it is not possible to carefully construct a valuable pattern over several turns: other players can finalise the pattern and score the majority of the points! The personal warehouse is off limits to other players, so it can be used to store some important blocks until you need them. The warehouses can contain only one layer of blocks, while the construction areas can contain up to three layers. A new layer can only be initiated when the previous layer has been fully completed! The game is over when none of the players can make a move. At first glance, Qubix sounds extremely easy: just create some patterns on your construction area. At second glance, it suddenly seems impossible: everything you try to accomplish can be finalised, or completely ruined, by another player. But during the game it all falls into place! The game is much more subtle than you would have imagined. Instead of forming them from scratch, patterns can also be created by covering certain blocks in the previous layer. And you can strategically lure your opponents into building on your construction area: at least you also receive some points when they score, but when they build solely on their own construction area they score alone! Since the details of Qubix become apparent only during the game, it should definitely be played at least twice. Barbara van Vugt Qubix, Adam Kaluza, Granna, 2012 - 2 tot 5 spelers vanaf 7 jaar, 45 minuten.xxtop |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

| c | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Rapa Nui | ||||||||||||||||||||||

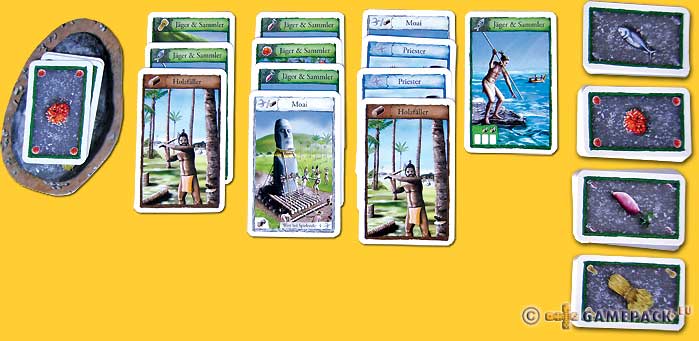

| 23.11.11 What happened at Easter Island will always be a mystery, but two two four players try to map out the events, each starting the game with a hand of four cards. From these, the woodman already is placed in front of them, thereby setting the tone of the game: there will be a lot more of this woodcutting! In each turn one or more cards are played, refilling the hand to three from a display that at the start of the game is four column wide, and four rows long. When a column gets depleted, it gets immediately refilled with four cards from a draw pile. When the draw pile is depleted, the game ends. When a player has taken one or more cards to refill his hand, the last one he took triggers a score for the card that is underneath. Players with the same card in their display may take either offer cards (fish, grain, sweet potatoes, flowers), points or wood, depending on the card. When a player wants to build a moai he plays the card and turns in seven wood, and when built, each player has to play an offer card from their hand, the building player offering two cards instead of one, with the second one coming from the general deck of offer cards. Moai score four points at game end, but the offer cards a player has in his hand also score, related to their amount at the sacrifice spot, from three to zero points per card. 'Rapa Nui' is a pleasant fast and elegant card game that also plays well with two players. Playing a priest, and taking direct point during the game? Or rather play the flower girl to achieve a majority over other players and collect two offer cards instead of one each timne when the flowers are scored, thus collecting more of these cards in the hope they will score the maximum of three points per card at game end? The consideration which card to play, and which to take, thereby scoring the underlying card, gives the game an interesting and tactical element. 'Rapa Nui' has in short time become a much played favorite: fastly set up, and swiftly played! Well done, Klaus-Jürgen! Rapa Nui, Klaus-Jürgen Wrede, Kosmos, 2011 - 2 to 4 players, 10 years and up, 40 minutesxxtop |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

| c | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Plateau X | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| 03.03.11 How simple can it be? Two to four players alternatively place a brick piece on the board or they move their pawn to a higher or lower level. At the end of the game the player whose pawn is at the highest level has won.. Easy, innit? Well, that depends. To get to a higher position than any other player requires some strategic insight; it is harde than one might think and before a player gets the message, he has manouvered himself into an awkward position. When a player moves his pawn he may move it over several levels with three not unimportant exceptions: the level to be entered must be directly adjacent to the position of the pawn -so no movement before towards the edge is allowed, the level to be entered must be one level higher or lower -no more, no less- and levels already occupied by a pawn of an other player may are no go areas. So, a player who wants to get his pawn to a higher position first has to place a brick piece adjacent to his pawn, or the pawn must be in such a position that it can reach the higher level by the aforementioned stepping stone movement. But ofcourse an other player can do this in his turn as well once the brick piece has been placed -thank you very much!- by moving his pawn to the higher level before the other player does. 'Mmmh, if I think you will do that, I will do this first': placing a brick piece adjacent to the pawn of the other player so the height difference is more than one. 'Rats!' the other player thinks, 'so this entry has been shut in front of me; let's see if I can build in such a way that I can reach it from another side - the backdoor maybe?'. And so player's thoughts continue, making plans, trying this or that, sometimes even setting up kind of traps. The game ends immediately when a player cannot place a brick piece and he does not want to move his pawn; the player having his pawn at the highest position has won. When tied, the player wins who was the first to have his pawn at this position. Admirers of a challenging strategic and short game should right walk to the pay desk to checkout this jewel! Plateau X, Hendrik Simon, Winning Moves, 2010 - 2 to 4 players, 10 years and up, 30 minutesxxtop |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

| c | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Revolution! | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| 04.05.10 Revolution! This sounds really exciting, like a spring clean! This time we are going to do it totally different! Preferably our way! Reality is that this soon turns out in sheer terror, and it doesn't really gets clean of all the clotted blood either. Well, what a nice theme we have here! Luckily in 'Revolution!' we deal with the revolution and the involved change of powers in a more abstract way by occupying various locations in the city. The revolution can be called succesful on our part if we have been able to put our stamp upon it and occupy the most important buildings with a majority, and scoring the accompanying points for it. With this we are glad that we are back on home-ground: planning actions and placing tokens. This planning in fact is done by bribing, black mailing or using physical strength on the various characters on the player board, and all players get a handfull of money, blackmail and force markers at game start. These markers are placed secretly and simultaniously on a maximum of five out of twelve characters. Will a player try to make the general his stooge? Using physical strength does not impress him, but maybe he is sensitive to blackmail? When all players have finished placing their markers, the results are revealed and the board is worked. The player who has placed the most markers on a given character, may perform its action. Often this is the placement of a player token at a specific location, together with one or more victory points. Often force markers, black mail markers or money can be collected that can be allocated in a following round. The spy and the pharmacist enable a player to change, remove or place tokens on a location. The game ends immediately when all locations are full with player tokens. The player with the majority in a location gets the points for it, and the player with the most points wins the game. Here's why 'Revolution!' doesn't work: players have to allocate all the markers at their disposal; withholding one or more for a future round is not allowed. All means go back into the supply, even when a player did not win the character and therefore could not perform the action nor in a tie where all players forfeit the right to play the character - the chits go the supply. This could lead to the situation where at an early stage of the game a player, by mere luck - because of the blind bidding - wins all or most of the characters, thereby effectuating a sequence where he over and over wins the bets over multiple rounds. Empty handed players start a round with five gold from the supply, but these are only of limited use as there is a rank in bets: first force, then blackmail, and only then money. This way, players starting a new round with only money will have a great chance of missing out, and often: again. Playing for a majority suggests tactical play, but with the use of the spy it is possible to remove a player's token and replace it by one of your own, even if this location is already full. The same goes for action of the pharmacist. This makes all planning totally useless, and players are left with the feeling: why bother? Even in the last turn there is the possibility of a change in majority. It does not happen that often, but all players, like real bourgeois, had the sighing: revolution, once but never again! Revolution!, Philip duBarry, Pegasus Spiele, 2010 - 3 or 4 players, 10 years and up, 45-60 minutesxxtop |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

| c | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|

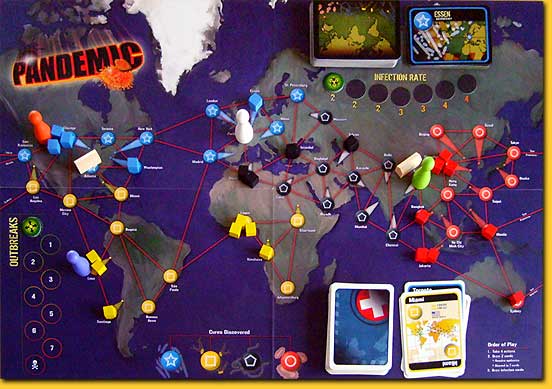

Pandemic | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| 18.04.08 Thunderbirds are go! The world must be saved! Deadly viruses walk about, and it is up to us players to counter this danger as a team. This will be done in a precise and military operation, where hopefully we are in time to put down all sorts of bird flu, chicken plague or mortal ant cough, and afterwards we are invited at the castle of the World President and his wife to be his guest for a week as a reward for the effort. Well, we just make up this reward, as the rules merely state the imminent danger we are faced with. At the familiar map of the world several cities are depicted, connected by a network of lines. Along these lines the viruses spread, and we as players move along these same lines. At game start some cards are drawn to indicate the infected sources. Each player gets a character card that has a special ability. City cards can be used to fly to a city, but of course it is cheaper but slower to walk along the lines. The two city cards a player takes in his hand at the end of a turn can be used to develop a vaccine: five city cards of the same colour and a players pawn in one of the research centers, and the first part of the battle is won. After the development of a vaccine each player in his turn may spend an action to suppress the virus. When all cities infected by that virus have been cleared, the virus has been eradicated and will not show up again, as after each player turn infection cards are drawn: at start only two, but after each epidemic (card) one additional. After such an epidemic mostly already infected cities get an additional cube to indicate the increase of the infection. If a city would get more than three cubes, the virus spreads along connected lines to all adjacent cities which now all get an additional cube of that virus. This may result in a chain reaction if the receiving city would also exceed the three cubes limit - now there you have the problem our team faces in a world cup! Time flies by, and if eight outbreaks have occured it is Finito, The End, all lost, and mankind as we know it from a famous tv series has ceased to exist. This also happens when the city card stack is depleted, so we need to move on and work together well! For Pandemic, we might not have been thouroughly clear about this, is a game players play as a team against the game system. Normally games of this kind are kind of dull, with little to none challenge. This game system however, is very cleverly designed, and the Thunderbirds feeling (yes, it exists!) to save the world from disaster is well present: 'Now if you take the charter to Dubai, I could give you the needed card for Paris. In the meantime Marijn builds a research center somewhere in your vicinity where in next turn you could invent the blue vaccine. Barbara as a medic then could swipe clean some dangerous spots, as in San Francisco the situation is highly critical. Now let us just hope we will not have another epidemic...' Brains, any further suggestions? Pandemic, Matt Leacock, Z-Man Games, 2008 - 2 to 4 players, 10 years and up, 45 minutesxxtop |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

| x | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|

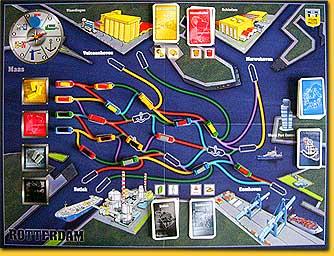

Rotterdam | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|

26.07.07 In the harbour of Rotterdam, until ten years ago the largest in the world but now ‘only’ the largest in Europe, there is a lot of activity. It is a nice idea to use this as a topic for a game, promoting the brand ‘Rotterdam’ at the same time. |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

| x | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Ponte del Diavolo | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| 04.04.07 My wife sees things, really! She sees 'em when we play Zèrtz, when we play Dvonn or Hive, and lately she sees 'em during Ponte del Diavolo too! Oh yes, I see 'em too, occasionally, but not as often or clear as she does. It really frightens me, or frustrates me, to be more exact. The case is that she sees tactical possibilities that I fail to see, or only see when it is too late. Frankly speaking, I have to acknowledge her superiority in these abstract games. Notwithstanding this, I keep a good heart each time I play such games with her, not in hoping to win, but to keep the score as close as possible to hers, and, in a next game, try to decrease this gap. This is my private war, my agenda, with my own targets, because any hopes to win from her in these games are futile. But it is so simple, even this time: in a turn, place two stones on the board, or place a bridge. Four adjacent stones form an island which is worth 1 point; connected with bridges these score more in the known string: 2= 3, 3= 6, 4= 10, and so on. An annoying restriction is that an island may not grow larger than four, and stones of the same player may not be placed diagonally next to these islands either. Further, stones may not be placed underneath bridges, and bridges may not be placed over stones. Simple, eh? It is because of this simplicity that gives the game its strength, together with its sober but wonderful execution; it could as well be a Japanese game! This makes it strange, why the publisher chose to put a rather carnivalesk illustration on the box cover - as Venice stands for magic? But it could as well be that the target group does not get reached because of this. Why not show the beautiful game as it is, in all its simplicity - show the potential buyer there is a wonderful, abstract, fascinating game inside, by giving the box front a more suitable cover. And if I could win the game only once, sometime in the future, I am satisfied even more... Ponte del Diavolo, Martin Ebel, Hans im Glück, 2007 - 2 players, 10 years and up, 30 minutesxxtop |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

| x | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Portobello Market | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|

25.2.2007 In Portobello Market you are not a mushroom merchant, but a stallholder on the biggest and most famous antique market in the world. For over three hundred years all kinds of antiques and antique like items are being sold here. In the game it is your job to get your stalls on the most lucrative places to score the most victory points. The board shows a map of the market area with streets that connect eleven market squares. A player starts with stalls in his colour and action chips of 2, 3 and 4 value. In his turn a player decides how many actions he wishes to take by turning over the corresponding action chip. There are two kinds of actions: place one or more stalls in the streets, or place a customer on one of the squares. Stalls can only be placed in roads that are directly attached to the district the bobby is in; a district is an area enclosed by streets. The bobby can be moved freely during a player’s actions, however this can cost him victory points when he does not have the majority of stalls in the street the bobby crossed. Instead of placing stalls a player can also place a customer which is blindly drawn from a bag and placed on an empty square of his choice. The two types of customers, poor or rich, decide the scoring factor when a street has been fully built with stalls and has customers at both ends; all players with stalls in the street then score points for the value of their stalls. Twice per game a player may claim a district instead of taking his regular action by placing one of his action chips in a district of his choice. He then gets points for his stalls from the adjoining streets in the district multiplied by the placed action chip. When only one empty square on the board is left, the richest customer, ‘the lord’, is placed there and gives the highest possible scoring factor for all streets leading to this square. At the end of the game, when one player has placed his last stall, all not fully occupied streets in connection with the lord are scored, other not fully occupied streets elsewhere on the board do not score. The actions in Portobello Marker are simple and transparent, which makes the game very accessible for inexperienced gamers. However there are enough tactical choices to be made, which also makes it an interesting game for experienced gamers. This could be a possible SDJ candidate! Marijn Vis |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

| x | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Pillars of the Earth | ||||||||||||||||||||||

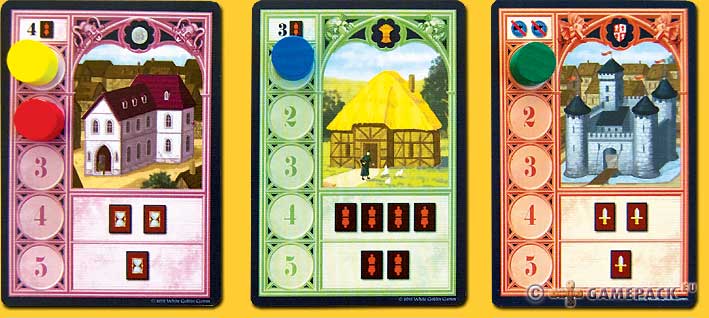

| 07.10.06 Two to four people participate in building a cathedral. At game start, each player gets three laborers: a mortar mixer, a carpenter, and a mason. These laborers are used to turn the collected resources in a round (sand, stone and wood) into victory points, necessary to win the game. Resources may be collected by picking one or more worker cards from a open set of seven cards; two other cards are new laborers that can be bought from the initial 20 gold. A player may have a maximum of five laborers working for him. The worker cards show a number in one of the three resources that can be claimed with a varying number of small wooden worker tokens; each player can assign all 12 of these every round and place them at the appropriate quarry or in the woods. Left overs, when not enough workers are left to 'buy' a worker card, are placed at the wool manufactory. After this, the starting player draws one builder token at a time from a cloth bag; each player has three of these in his players colour. The first player drawn must pay 7 gold to place his builder on one of 14 locations on the board, or pass and leave his token momentarily on the '7' spot. The second player pays 6 or must pass, etc., untill all paying players have placed their builders on the board or have passed. After this, all passing players may place their left over builders, one by one, for free. Then, in chronological order, all actions on the 14 locations on the board are carried out. First, an event card is read out loud that affects all players, except the one player that has placed his builder at this location. The resources now may be collected, and the players get their workers back for a following round. Taxes must be paid too, and the players that did not place a token at the King's location, must pay from 2 to 5 gold, decided by the roll of a die. There are locations where privilege cards can be taken, some of them have an immediate effect, others may be saved for a future round or occasion. At the village are two labour cards; one for each player that has placed his builder there. At the market additional resources may be bought or sold, and finally, the starting player ends the round by placing one of the six wooden parts that form the cathedral. After six rounds the game ends. Players constantly move between decisions like pumping up their gold, or converting the resource cubes into victory points, and this is what the game makes fun. Adding certainly to the atmosphere of the game are the beautifully illustrations by Michael Menzel; the mapboard is full of detail. The labour cards could be seen as an example of a romantic Soviet view of the labor classes, but this is not meant to be critical at all, the illustrations are simply very well done! There is much more in the game that has not been said; we keep that for a full review. But what kind of game is it? The 'collecting scarce resources and trading them in for something more valuable-game' resembles many other games. But because of this familiarity players instantly feel comfortable when playing the game, no matter if it resembles 'Game X-Light' or 'Game-Y Medium'. The parts of the cathedral are only used to mark the starting player of a round, they serve no other function. But again this is not to be taken negative, would it have been left out, it would have felt somewhat strange for a game on cathedral building. And it feels good to see a publisher who puts superfluous material in a box! Two players are done within 90 minutes; four players need some twenty minutes more. After that, we are left with the feeling that we have experienced a very good game, maybe even one of the highlights of this year. Pillars of the Earth, Michael Rieneck & Stefan Stadler, Kosmos, 2006 - 2 to 4 players, 12 years and up, 90 - 120 minutesxxtop |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

| x | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| x | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| x | |||||||||||||||||||||||